I am even tempted to say that the proposed trail does not follow best practices, but trails beside major highways are not the common. The consequence is that best practices have not been developed for such highways. However, this does not mean that the design of a bicycle trail can ignore all the best practices for general trail and separated bike lane designs in the professional literature and the recent recommendations of government organizations such as the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA 2015). The trail does meet the minimum guidelines for the Commonwealth of Virginia, but in some cases the project seems to have been granted exceptions from even those guidelines. This post was based on a white paper called The Missed Opportunities of the Transform I-66 Bicycle and Pedestrian Trail.

Critics of the Design of the I-66 Trail

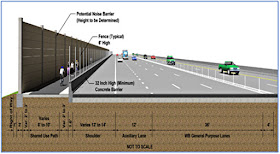

The existing trail design has many positive aspects, but it also has many problems. These have been highlighted by bicycle advocates in both Virginia and Washington, DC. An article in the Washington Post titled, Biking advocates worry I-66 expansion project puts a bike trail too close to traffic, highlights some issues on one part of the trail. Other concerns have been published elsewhere by the WashCycle, the Washington Area Bicycle Association and the Fairfax Alliance for Better Bicycling, but I will cover them in this section.About 3 miles of the trail is placed inside the sound wall beside high speed highway traffic making it an uninviting place to bicycle, walk, or exercise (figure 1). The sound wall will reflect sound back onto the trail and trap pollution from the adjacent highway.

The trail has sections that make bicyclists and pedestrians travel further than a car on the I-66 highway. Connecting the trail to other local attractions and bicycle infrastructure was not given priority. The W O and D, a major bicycle trail, is only one mile from the end of the trail.

Gaps exist on the trail, and it appears bicyclists and pedestrians will be diverted onto roadways. Perhaps these roadways will be treated with bicycle lanes, but it takes away from the direct nature of a bicycle trail. It’s left to others to make connect gaps in the trail. The trail for the most part is on one side of the highway. A trail on both sides would mean greater access by local populations.

The bicycle trail will be a maximum of 10 feet wide, with a 2 foot wide shoulder on each side. In some space constrained areas the trail will be 8 feet wide. Current Federal Highway Administration guidelines recommend that 12 feet is preferred for bidirectional bicycle and pedestrian paths (FHWA 2015). Also, if possible pedestrians should be separated from bicyclists.

The I-66 Express Mobility Partners who will build the bicycle trail will not collect fees on the trail, so they may have limited incentives for producing a state of the art trail.

|

| Figure 1. Design of the I-66 Trail Inside Sound Wall (Source: VDOT) |

Due to the unique circumstances of threading a bicycle trail along a major highway in the middle of a densely populated corridor, there have been few best practices to fall back on in the process of designing a major bicycle trail. When push comes to shove in critical areas of the trail, the interests of bicyclists and pedestrians seem to have been sacrificed to the overall goal of widening the highway.

The Best Practices for Bicycle and Pedestrian Trail Design

No manual for bicycle and pedestrian trail design beside major highways existing. They are quite diverse and coming up with common solutions to a wide state of conditions has been difficult. In fact a review of the literature indicates that only one study has seriously considered the issues. This is a study done by ALTA Planning and Design and State University of New York at Albany called Shared Use Paths in Limited Access Highway Corridors.After reviewing several studies and based on my own experience, properly dealing with the following characteristics make the difference between bicycle and pedestrian trails that will be used extensively and those that will be used only by dedicated cyclists. I may be leaving out some aspects, but here is an attempt to summarize best or good practices for bicycle and pedestrian trail design.

Separation: Separation is needed between high speed highways and bicycle and pedestrian trails. No one wants to be walking, jogging or bicycling along a busy highway with noise, water spray, pollution and close in spaces defined by high fences. The standard of over 10 feet is adhered to of the case of the I-66 project, but the fences surrounding parts of the trail give a feeling of claustrophobia for pedestrians and cyclists. The trail should be separated either by grade or by a barrier wall. The most interesting design example of this is the Glenwood Canyon Bicycle Trail which locates the trail below the highway and beside the Colorado River (figure 2). The Canyon is quite narrow so the trail was located below grade next to the Colorado River rapids along much of the trail. With cars and trucks whizzing above, there is surprisingly little traffic noise.

|

| Figure 2. Glenwood Canyon Bicycle along Colorado River (Source: Trip Advisor) |

The design of the new Frederick Douglas Bridge has bicycle lanes on both sides that connect to the Anacostia Riverwalk Trails on both sides of the river. The pedestrian and bicycle path follow or exceed current best practices. The bridge has bicycle and pedestrian lanes on both side of the highway. The bicycle lanes on both sides are 10 feet wide and the pedestrian lanes are 8 feet wide, for a total width of 18 feet. Counting the lanes on both sides of the highway, there is 36 feet of space for pedestrians and bicyclists on the bridge. The contractors for the bridge made a real commitment to multimodal transportation after the District of Columbia government indicated that the project should seriously consider multimodal transportation in the design of the new bridge.

|

| Figure 3. Design of New Frederick Douglass Bridge, Washington, DC (Source: District Department of Transportation) |

To mitigate the problems of speed, a bicycle trail that is really separated does not have to worry about adjacent traffic. A 10 mile trail from Tampa to Clearwater Florida goes over Tampa bay. Some portions of the trail on land are adjacent to the highway and the (figure 4), but the part that goes over the water actually has a separate bridge built especially for bicyclists and pedestrians. The trail over the water is totally separated from the highway. The trail ranges from 8 feet wide to 12 feet wide.

|

| Figure 4. Courtney Cambell Causeway Trail, Clearwater-Tampa, Florida (Source: Trip Advisor) |

The I-66 trail has gaps and leaves development of some aspects to future projects managed by different agencies. When the Capital Crescent Trail was first opened, there was a dangerous crossing at River Road. After several accidents a bridge was constructed to cross River Road. Such bridges cost about $3 million, depending on design, so they are well worth the trouble of keeping the trail connected.

The US is far behind countries such as the Netherlands in creating protected intersections, but we are finally starting to invest in them. I’m not sure why it is taking so long to adopt a best practice, but in all likelihood it involves both expense and an ingrained car culture.

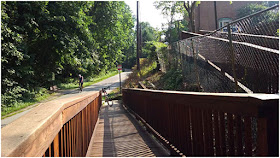

Connections: Bicycle and pedestrian trails have greater traffic and higher benefits when connect to other trail infrastructure. The I-66 trail concentrates mainly on the corridor and relegate the connection of the trail to “coordinated” programs. Connecting neighborhoods is a major design challenge for a major trail such as the one along the I-66 corridor. Instead of creatively tackling the issue, the project either makes compromises such as locating the trail inside a wall or leaving it to other local jurisdictions to deal with the problem. Evidence suggest that once well designed and maintained trails are constructed through neighborhoods, people love them. Such trails even become a major selling point for homes and apartments near them. One section of the Legacy Trail in Venice, Florida has built "Stations" to denote connection to the neighborhoods and parks along the trail (figure 5).

|

| Figure 5. Legacy Trail Station and Neighborhood Connector Trail, Venice, Florida (Source: Doug Barnes) |

|

| Figure 6. Residential Complex Connection to Capital Crescent Trail, Bethesda, Md. (Source: Doug Barnes) |

Possible Lost Benefits Due to Poor Multi-Use Trail Design

The main problem with the I-66 bicycle and pedestrian trail design is that due to the unpleasant environment along many parts of the trail, its use will be quite limited. This also means that the traditional benefits attributed to bicycle and pedestrian trails will be curtailed as well. The main benefits of bicycle trails has been covered in another post, so they only will be summarized here. A well designed trail will lead to the following benefits.- Increase in real estate value for homes in close proximity to the trail;

- Improved air quality from encouraging commuting by bicycle or foot;

- Reduction in commuting expenses due to bicycle commuting;

- Increase in sales for businesses near the trail;

- Health benefits for the people using the trail; and

- Better physical environment if trail is developed into a linear park along the corridor.

With the proper design, the Transform I-66 has the same potential to change the area surrounding the corridor. This also could probably be done within the budget with minimal or perhaps slight increase in costs. However, the transportation planners would have to think more creatively the proposed trail design in the existing project. Yes, the corridor widening work is the main focus of the project, but with a little creativity the project could do so much more for bicyclists and pedestrians. In addition, a quality bicycle and pedestrian path would take cars off of I-66 and improve traffic flow.

A major benefit of a better designed trail would be an increase in property values in proximity to the trail. A general objection to most proposed bicycle trails is that they will lower property values. However, the evidence suggests that once the trails are built, the neighborhoods understand the positive benefits of the trails (see Annex 1 for literature review). Children will be able to use the trail to get to friends’ houses and part of the way to school without being bothered by cars. People looking to move into the area generally are looking for good schools and parks. Many consider a walking or bicycling trail as a top amenity for a neighborhood. The demand for housing near the trail increases and this results in a price increase. This is an indirect outcome of the actual benefits of the trail that are valued by homeowners and those living in close proximity to the trail.

The design of the trail along the I-66 Corridor is still not completed, but in its current configuration it probably will not draw as many riders and pedestrians as it should. Opportunities exist to address some of the major issue facing the trail. For instance, the placement of the trail inside the sound wall and making the trail double as a service road will make riding on the trail unpleasant. The detours onto away from the main corridor onto local roads will mean the trail does not facilitate a smooth flow from one point to another. The lack of entry points for neighborhoods will mean that the trail will not be able to connect neighborhoods. The narrow nature of the trail in some points meets only minimum requirements for trail comfort for both pedestrians and bicyclists. Awkward passage through trail intersections with major roads will further diminish the attractiveness of the trail. All these issues can be addressed, but more work is necessary on conceptualizing the design of the trail and working with local partners to assure an attractive and beautiful bicycle and pedestrian thoroughfare.

Recommendations

This is not to say the trail should not be built even in its current configuration. The issues is the unrealized benefits of the trail. Making the trail more attractive to everyday citizens and even children will significantly increase the value of the Transform I-66 project in the order of hundreds of millions of dollars. The trail as it is currently designed will have value, but it will be nowhere close to an improved trail that features connection of neighborhoods, connection with other local trails and a wide enjoyable experience for all in the community as opposed to just dedicated cyclists. Given that the design contracts are still to be given out, several recommendations are possible for an improved design of the trail that will make it attractive for a wide variety of bicyclists and pedestrians.The first is a bicycle and pedestrian advocates in VDOT needs to be fully responsible for oversight of the trail portion of the project. I have tried to find detail of the trail, and have only come up with a few maps and design principals. The trail is to be built by a quite complicated amalgam of entities responsible for designing and constructing the trail, including the Express Mobility Partners, Northern Virginia Regional Parks Authority, Fairfax County Parks and the George Snyder Trail project. In addition, there appear to be some gaps in the trail in which bicyclists and pedestrians will be directed onto local roads. No plans as yet have been developed on how these segments will be configured. A bicycle and pedestrian full time advocate within VDOT is necessary because in such project the trails do not get as much attention as the major highway portions of such projects. Traffic and highway engineers are not trained to design bicycle trails, so internal advocacy is necessary to fully bring key multimodal issues to the forefront of the project design and implementation.

Second, the trail needs to be designed as part of an overall bicycle and transportation plan for the county and not as it appears now as just an add on to highway project. The advocates within VDOT should coordinate with other agencies and non-governmental organizations advocating multimodal transportation within the region that will be responsible for other portions of the trail to make sure best practices are part of the overall project. For the gaps in the trail it is no enough to paint lanes as this will lower the use of the trail. There will need to be a feeling of safety on the portions of the trail that are not dedicated to bicyclists and pedestrians. It is clear that meetings are planned for public consultation about the highway design, but they seem after the fact for the design of the bicycle trail. In order for a state of the art trail to be constructed, the Virginia Department of Transportation will need to give directives to the contractor to cooperate with other agencies and design a trail that is befitting of the name Transform I-66.

Third, it is recommendation that as part of the road design process a good multimodal design firm such as ALTA Planning and Design do a serious study of the possibilities for an innovative trail along I-66. It will not be enough to have a highway design contractor design the bicycle and pedestrian trail. They are quite competent for the road design, but would generally lack the expertise in multimodal trail design. In addition, they would have little competence in working with local groups to incorporate community input into the project. This could be part of the terms of reference for any contract for the design of a bicycle and pedestrian trail for the I-66 corridor.

Fourth, the most recent recommendations of the Federal Highway Transport Administration and other agencies need to be incorporated into the project. This could be part of the terms of reference for the study to be conducted by a multimodal planning contractor. The design standards have been changing in recent years. In 2015 the Federal Highway Administration came out with guidance study for separated bicycle lane design (not including pedestrians). The preferred width for two-way separated bike lanes is 12 feet (FHWA 2016, pp. 80-81). For single direction bike lanes the preferred width is 7 feet.

Fifth, a hard look is necessary for placing the trail within the sound wall. This has been the flashpoint for local bicycle organizations, but the trail design also suffers from other problems such as gaps, separate funding by different agencies, and separate designs by different agencies for their portions of the trail. This may be the most convenient and least costly method of construction, but it will lead to tens of hundreds of millions of dollars of lost project benefits. The reason is that traffic noise, air pollution, visual unpleasantness and lack of access to the trail will curtail trail users and lower the economic value of the trail.

In the words of the Fairfax Alliance for Better Bicycling, “It is exciting that current plans for I-66 Outside the Beltway include the parallel trail and bike and pedestrian connections on all rebuilt bridges, but we want to make sure it becomes a reality!” The trail along I-66 has the potential for being transformative for the many neighborhoods, towns and communities within the corridor. The current design would suppress the use of both the trail and its benefits. A properly designed trail will lead to increase in pedestrian and bicycle use, increases in property values, expansion of the development of businesses and others. Such a trail will have substantial value for all those living in the vicinity of I-66.

Annex 1 Review of Literature for Property Values Surrounding Trails and Greenways

This is a summary of the literature review on real estate values and trail proximity conducted for a study on The Benefits of the Extension of the Legacy Trail in Sarasota County, Florida. The full report is The Value of the Legacy Trail Extension for Sarasota, Florida. The following is an excerpt from that report.Various studies have found that real estate values surrounding a trail or greenway increase for those houses within one-half mile to over a mile from the trail. The case with demographics similar to the Legacy Trail Extension is the Little Miami Trail in Cincinnati (Parent and vom Hofe 2013). During peak months, this trail has 75,000 visits. Although the trail is 78 miles long, the authors confine their analysis to the last 12 miles entering suburban and downtown Cincinnati. Thus, the situation analyzed is quite similar to the Legacy Trail Extension.

The Little Miami Trail study uses assessed real estate values as the dependent variable and controls for such factors as home size, distance from city, number of rooms, and distance to a trail entrance. The study found that the trail influenced real estate values as far as 10,000 feet from trail entrances. However, real estate closer to the trail entry points had even higher values. For convenience, the study mean of 5,772 feet distance of houses from the trail entrances is used as a baseline for estimating the value of houses closer to the trail. The findings reveal that those houses within 0.10 miles have an increase in value of close to 8 percent above the study mean distance from the trail, and those within a quarter mile improved in value by 6.5 percent for the mean value of houses along the trail.

In a study for San Antonio, Texas, Asabere and Huffman (2009) examine the relationship between various types of community amenities and real estate values. This study does not focus exclusively on trails as it also includes playgrounds, tennis courts, and neighborhood pools. As its dependent variable, the study examines residential sales of real estate in Bexar County, Texas for one year (April 2001 to March 2002). During that period, the total house sales numbered 10,000. The variables measured include the characteristics of homes, geography, and other factors. The findings indicate that, even after controlling for other factors, the impact on home prices is 2 percent for trails alone, 3 percent for greenways, and 5 percent for greenways with trails.

A study of multiple trails in Indianapolis found that some trails have a greater impact on real estate values than others (Lindsey et al. 2004). In particular, the study found that the Monon Trail—the one most similar to the Legacy Trail Extension--had the highest impact on home values. The trail is 24 miles long, connecting Indianapolis to its (northern) suburbs. Within one-half mile of the trail, home values increased by 14 percent ($115 million in 1999 dollars and 167 million in 2017 dollars). The popularity of the trail has continued to increase, and today there are over 1 million users each year. Recently, the town of Carmel, Indiana (north of Indianapolis) announced it will spend $23 million to upgrade the trail from a 12-foot path with few surrounding amenities to a 140-foot corridor with bike lanes, sidewalks, one-way streets, greenspaces and parking spaces (Sikich 2017). However, some of the other trails in the study did not have the same impact as the Monon Trail, indicating the importance of trail location on the economic impact of projects.

The economic value of the trails in Mecklenburg County (Charlotte) in North Carolina was studied to estimate the benefits for a proposed new trail called the Catawba Regional Trail (Campbell and Munroe 2007). Some of the trails in the study are similar to the Legacy Trail Extension, but others differ dramatically. The residents in homes near some of the existing trails in Mecklenburg County are quite poor. Median household income is about $50,000, and the value of the average single-family home near the existing trails is $106,000. The economic impact study estimated the increase in real estate values because of existing trails in the county. Within 5,000 feet of the trails, the real estate value increased by 3.1 percent. It is likely that the rate was higher within one-quarter mile of the trails. Unfortunately, the planned Catawba Regional Trail was never completed; instead, the financing of other trail fragments took priority.

References

Asabere P., and F. Huffmann. 2009. “The Relative Impacts of Trails and Greenbelts on Home Prices.” Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics 38(4):408–19.Campbell, Harrison, and Darla Munroe. 2007. “Greenways and Greenbacks: The Impact of the Catawba Regional Trail on Property Values in Charlotte, North Carolina.” Southeastern Geographer 47(1): 118–37.

Lindsey G, J. Man, S. Payton, and K. Dickson. 2004. “Property Values, Recreation Values, and Urban Greenways.” Journal of Parks and Recreation Administration 22(3): 69–90.

Federal Highway Administration, US Department of Transportation (FHWA). 2015. Separated Bike Lane Planning and Design Guide. Washington, DC.

Parent, Olivier, and Rainer vom Hofe. 2013. “Understanding the Impact of Trails on Residential Property Values in the Presence of Spatial Dependence.” The Annals of Regional Science 51(2): 355–75.

Lazo, Luz. 2017. “Biking advocates worry I-66 expansion project puts a bike trail too close to traffic.” July 9, Washington Post, Washington, DC.

No comments:

Post a Comment