|

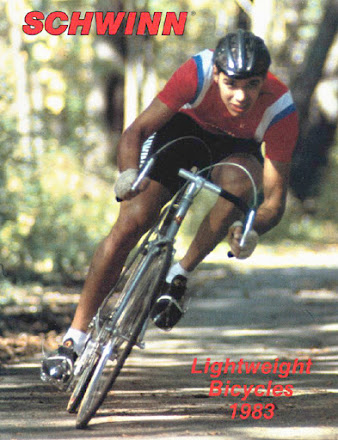

Schwinn Lightweight Bicycles, 1983 (Photo: Schwinn Bicycle Company 1983) |

My interest in Schwinn bicycles started in childhood. As a child, I never owned a Schwinn bike but I learned about them from others in my neighborhood. These bicycles had a reputation of being very rugged. Families not only passed them on from one son or daughter to another but sometimes they survived and were used by subsequent generations. I also worked in a Schwinn bicycle shop in the 1970s and I became very familiar with the Schwinn brand. I recently rebuilt an old 1983 Schwinn Le Tour and the article had been quite popular.

Also, this is a long read despite the title. I use the term short history because so much "long history" has been written about Schwinn. Schwinn Bicycles lasted as a family company from the 1890s until 1992. It was then taken over first by venture capitalists and today is owned by a bicycle company that manages such brands as Cannondale, Iron Horse, Mongoose.

Richard Schwinn wanted to stay in the bicycle business but he was prohibited from using the family name. With a partner, he purchased the custom manufacturing Paramount factory in Waterford, Wisconsin, His company still makes high-end bicycles today under the Waterford name.

This is the full history of Schwinn as a family company from 1895 to 1992. I also have separate posts for different time periods that are the same as those in this article. The reason for them is that many people don't want to skim through the whole history to find information on a particular time period.

Company Founded during the 1890s Safety Bicycle Boom

Once he arrived in Chicago he worked for a series of bicycle companies. He still felt that he was being held back. In 1894 he had a chance meeting with a fellow German immigrant named Adolph Frederick William Arnold. Arnold had an inkling that bicycles would have a bright future. Having first made his money in the meatpacking business and later as a successful investor and banker, Arnold could see the promise of collaborating with an innovative bicycle factory manager like Ignaz Schwinn. The consequence was the Arnold Schwinn and Company was formed in 1895. With a strong investor and an experienced manager, Arnold Schwinn & Company was off and running.

|

Possible Schwinn First Bicycle, 1895 (Photo: Famous Schwinn-Built Bicycle Brochure, 1895) |

The publication in 1895 coincides with the same year Schwinn was founded by Adolph Arnold and Ignaz Schwinn. This publication with the name Famous Schwinn Built-Bicycles very likely was marketing the original bicycles sold by the new bicycle company founded by the two founders. The brochure contains four interesting safety bicycles, including two for racing and two for everyday use. The racing bicycle is stated to be just 19 pounds. Because of the development of the safety bicycle, women had become avid bicyclists in the 1890s. The Schwinn women's everyday model has a rear fender and webbing seemingly designed to prevent skirts from getting caught in the wheel or the chain.

A Turn towards Motorcycles from 1900 to 1930

The bicycle industry entered the doldrums at the turn of the 20th Century. Adult ridership of bicycles plummeted as people’s attention turned to motorized transportation. The Wright Brothers started ignoring their bike shop in favor of flying machines. Henry Ford rode a bicycle to a factory where he manufactured his first motorcar that looked like two bicycles joined together. He and others like him working on the first cars would sound the death knell for the 1890s adult bicycle boom.

At the time, A. G. Spalding and Alexander Pope, both

major bicycling manufacturers, realized that adults were quickly moving away

from riding bicycles. With the slide in adult sales, Spalding and Pope joined

hands with some others from the bicycle business to form the American Bicycle

Company, a consolidated trust of manufacturers. In the spirit of industrial capitalism

at the turn of the century, the goal was to monopolize the market and to put small

independent bicycle companies out of business.

The venture almost worked. In 1899, the bicycle trust claimed to control

75 percent of bicycle sales. Over time, the major players in the trust began to

bicker and fight with one another. This combined with declining bicycle sales

caused the trust to burn through $80 million in startup capital. The well-financed

trust was a spectacular failure and by 1903, it went into bankruptcy.

Ignaz Schwinn wisely stayed away from the ill-fated trust

because he wasn’t one to surrender his independence. In the context of

declining sales, he knew that to stay in business, his company would have to change

its focus. He took advantage of the bicycle slump to purchase troubled

manufactures. His partner Adolph Arnold could see that bicycles were no longer a

growth industry. In 1908, he agreed to sell all his shares in the company to

Ignaz Schwinn. On his part, Schwinn never gave up on the bicycle side of his

company but he recognized that to survive his company would have to diversify.

Ignaz Schwinn knew his company had a problem. In the first decade of the 1900s, the sales

of bicycles to adults had eviscerated. The remaining bicycle sales that

remained during the slump were to children. Making matters worse, Schwinn had

to sell its bikes through department stores such as Sears and Montgomery Ward.

These retailers competed based on price and didn’t care much about quality

because there was no appetite for parents to purchase long-lasting bicycles. Bikes

did not have to last very long because children quickly outgrew them. Also, young

kids are rough on bicycles and they were ready for the scrap heap once they

were ready to move on to a larger size.

Ignaz Schwinn saw the writing on the wall. He would have to diversify to keep his

company alive. He made a bet on a new type of cycle—the motorcycle. Most of Schwinn’s

creative energy from 1910 through 1930 went into producing a well-respected

brand of motorcycle called the Excelsior. In 1917, Schwinn purchased Henderson

Motorcycle Company from its owners. Their

motorcycles were popular and in the late 1920s, Schwinn became the third

largest motorcycle company in the country.

|

| Schwinn Excelsior Bicycle 1917 (Image: 1917 Schwinn Catalog) |

A nice side benefit of purchasing Henderson was they also produced a line of bicycles that could be integrated into the Schwinn portfolio. In a sense, entering into the motorcycle business saved Schwinn as a bicycle company by getting through a very rough patch of declining sales. The motorcycle division of Schwinn took up all the creative energies of the company, and the bicycle division limped along barely surviving its plight. But by purchasing new bicycle companies during industry consolidation, intentional or not, Schwinn was positioning itself for the next phase of its bicycle business.

The good times of the roaring twenties led to the Great

Recession. The bubble burst and all companies, including the motorcycle industry,

came under great financial strain. Ignaz Schwinn was heavily invested in the

stock market and the plunge in the value of stocks left him with few financial

resources. Thus, in 1931, he called

together a group of his closest associates. He realized the time of Schwinn competing

in the motorcycle business had come to an end.

He could not find a buyer for the motorcycle business, so at the meeting

of his senior staff, he said, “Gentlemen, today we stop.” Schwinn abandoned the

motorcycle industry and in an unlikely gamble turned its focus to

bicycles.

At the age of over 70 years old, Ignaz Schwinn decided it

was time to wind down his active management of the company. He turned over business

operations to his son Frank. With the motorcycles in the rearview mirror, Frank

Schwinn took on the difficult task of reinventing what remained of the bicycle business.

The company would eventually be renamed the Schwinn Bicycle Company. With his

background as an innovative motorcycle engineer, he set his eyes on developing futuristic

new bicycle products geared towards children. The stage was set for an era of Schwinn

creativity and innovation that would catapult the company into a dominant position

in the bicycle industry.

Gamble on Promoting Style and Quality in the 1930s

Frank W. Schwinn was not satisfied that he had changed the

children’s bicycle market. He wanted to

make an even larger mark on the bike industry.

After another trip to Europe in 1935, he was delighted to see adults

riding bicycles. He was especially enamored with the sturdy internal 3-speed roadsters

he had seen gliding over the streets of England. He decided that Schwinn should

enter the adult bicycle market with a unique twist.

Frank Schwinn and his engineers got to work after his trip

to Europe. The team began to develop a new line of adult lightweight Schwinn

bicycles. Determined to once again reshape the bicycle industry as he had in

the early 1930s, Frank W Schwinn hired one of the USA's best-known bicycle race

mechanics name Emil Wastyn. With this collaboration in place, he learned that the

manufacturing process had to be radically realigned to produce bicycles for

adults. Under the supervision of Frank and his new lightweight bicycle engineers,

Schwinn began to produce light chrome-moly lugged frames along with finely

machine bicycle components that such as sprockets, hubs, cranks, and headsets.

|

| Schwinn Paramount Racer, 1939 (Image: 1939 Schwinn Lightweight Bicycle Catalog) |

As chronicled in the 1939 Schwinn catalog, Schwinn made the bold claim that,

With the production of these super-fine lightweight touring and racing bicycles, the United States of America takes its rightful place among the leaders of the fine bicycle manufacturing nations of the world.

In 1938, Schwinn christened

the top-of-the-line lightweight bicycle the Paramount. The Paramount was destined to be an iconic product but the line was never

very profitable. Frank Schwinn understood that the Paramount was a market leader that would set a high standard for all Schwinn adult bikes. To market

these bicycles, the company sponsored a successful Schwinn Race team to

participate in the popular 6-day races of the day. They also financed an

attempt at breaking the world speed record and succeeded. On a Schwinn Paramount in 1941, Alfred

Letourneur rode close behind a specially designed motor vehicle and he set the

world speed record at an incredible 108 miles per hour.

|

| Schwinn Paramount World Speed Record, 1941 (Schwinn Catalog, 1949) |

The Paramount was never the most profitable product for the company but it firmly engraved the Schwinn name into the annals of bicycle history. One goal of the Paramount line was to market the Schwinn brand as producing bicycles of the highest quality. This strategy would succeed and the Schwinn Paramount would become part of Schwinn's enduring legacy for quality and innovation until the company’s bankruptcy in 1993.

The 1930s was a period in which Frank W. Schwinn established himself as a creative force in both his company and the bicycle industry. The decade started with an emphasis on motorcycles and ended with Schwinn firmly established as the highest quality bicycle maker for both adults and children. The innovations of the 1930s, such as the balloon-tired children's bikes, front suspension, front drum-style brakes, and the Paramount Racer set the direction for Schwinn to next several decades.

WWII Pause and Pivot to Marketing in the 1940s

|

| Schwinn Manufactures Own Crankset, 1941 (Image: Schwinn 1941 Catalog) |

In the era of Rosie the Riveter, the composition of Schwinn’s

workforce also changed. Male and some female Schwinn employees were reporting

for overseas duty in large numbers. Schwinn adopted a policy to encourage the

family members of those leaving for military service to fill their vacant jobs.

Many mothers, wives, and sisters began

working on the Schwinn’s factory floor as their loved ones headed for the military

conflicts in Europe and Japan. During the war years, women became the main

workforce for Schwinn.

The end of the war brought with it better times both for Schwinn

and the country. The post-war years were an era in which new families were

being started. Soldiers returning from the front lines wanted nothing more than

to pick up the pieces of the time they had lost while they were in the

military. The resulting baby boom was followed by a surge of new spending on houses,

radios, refrigerators, washers, and consumer items.

During this fresh start, Schwinn turned its energy towards marketing

during this period of growth of consumerism. At Schwinn, the engineering

culture established in the 1930s had laid the groundwork for producing a variety

of new high-quality bicycles. Now in the latter part of the 1940s, the company with

its stable of high-quality products was poised for the coming increase in

demand generated by the return of war veterans. The question was how to sell

them.

The seeds for how to market Schwinn products were spread during

the 1930s. Frank W. Schwinn was eager to reduce the company’s reliance on large

retailers and had begun investing resources in developing direct relationships

with small bicycle dealers across the nation. The consequence of this shift was

that Schwinn had a pipeline of information about consumer preferences from those

on the front line of bicycle sales. By the end of the 1940s, Schwinn had reduced

its relations with large retailers and focused on its relationships with bike

shops. In 1939,

|

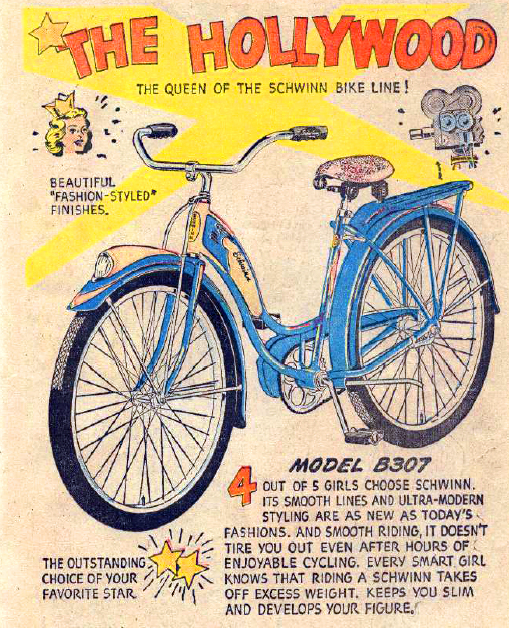

| Schwinn Hollywood Model Kicks Off Film Star Marketing Campaign in 1939 (Image: Schwinn Illustrated Catalog, 1949) |

Selling bicycles through smaller shops meant that that Schwinn had to develop its own marketing strategy. Schwinn boldly stepped out of its engineering comfort zone and recruited many of Hollywood's top stars to promote their innovative bicycle lines. The luminaries featured in the 1946 poster catalog included Dorothy Lamour, Roy Rogers, Ronald Reagan, Jane Wyman, Janis Paige, Barbara Stanwyck, Joan Crawford, and Bing Crosby.

|

| Dorothy Lamour Promotes Schwinn, 1941 (Image: Schwinn Catalog 1941) |

With a line of quality bicycles and a marketing strategy

fine-tuned to consumer demand in place, during the late 1940s Schwinn was off

and running. With the Hollywood stars endorsing Schwinn products combined with

its reputation for quality, their bicycles began flying out of stores. Schwinn increased sales to 400,000 bikes by

the late 1940s and by 1950 had a 25% market share of bicycles sold in the USA.

With the manufacturing capacities in Europe and Asia decimated, the company became one of the dominant bicycle manufacturers in the USA. Within two decades that included a pause for World War II, Schwinn did not miss a beat. Frank W. Schwinn had changed a failed motorcycle business and a floundering bicycle company into a powerhouse that was on its way to becoming an American cultural icon.

Becoming a Cultural Icon in the 1950s

Frank W. Schwinn was making all the right movies. His vision

for the company was either prescient or just plain lucky. Starting in the 1930s,

he turned towards building stylish bicycles with flashy chrome and marketing

them to kids. He also introduced a line

of state-of-the-art lightweight bicycles for adults that were way ahead of their

time. In an era of inexpensive cookie-cutter bicycles sold by large retailers, he

gambled that consumers would pay for style and quality. He pivoted Schwinn’s

reliance for sales through large retailers towards independent bicycle companies

that were more in tune with consumer bicycle needs. Finally, he tweaked Schwinn’s

“fair market” policies so that retailers could not compete against one another based

on price.

By the beginning of the 1950s, Schwinn was poised for

takeoff. The company was not alone. With the post-war baby boom in full swing, the whole bicycle industry was ready for growth. In 1946 when soldiers returned from overseas,

three and three-quarter million babies were born, one of the highest levels in

decades. This number would increase to over four and one-half million by 1955. All these children were primed and ready to

ride bicycles produced by Schwinn and other manufacturers.

For the children of the 1950s, bicycles were more than just

a toy. For them, the bicycle was a critical means of transportation and gave

them the first taste of freedom from their parents. Children could independently

ride around their neighborhoods, to a friend’s house, to pick up baseball

games, or to just hang out. With the increasing suburban sprawl creating longer

distances but safe low traffic volume streets, bicycles became something of a childhood

necessity.

Schwinn in the early 1950s had a 25 percent share of bicycle

sales, a level higher than any other brand. During the ensuing years, competitors

would begin catching up with Schwinn. But with overall bicycle sales increasing,

this was not a problem. Schwinn still increased its sales steadily from around five

hundred thousand bicycles in 1950 to over one million by the late 1960s.

|

| Schwinn Advertises Sales Dominance of the 1950s (Image: 1957 Schwinn Catalog) |

Schwinn also was in the process of refining its bicycle marketing strategies. The company hired an innovative marketing specialist named Ray Burch to liven up and better target their advertising. To better understand consumer demand, Schwinn also made it a point to listen to suggestions from its high-volume dealers.

Single-brand, authorized car dealerships were all the rage in

the 1950s. Schwinn decided a similar model would work for bicycles. Schwinn

began moving towards the idea of “Total Concept Stores” which eventually became

“Authorized Schwinn Dealerships.” By happenstance, this had been a position

advocated--but not fully adopted--by Frank W. Schwinn in the 1930s. It was not until

the 1950s that his desire to break from large retailers would come to fruition.

The idea of moving towards dedicated bicycle dealers was

reinforced by a visit of Ray Burch and his marketing team to a bike shop in California owned by George Garner that

was selling Schwinn’s like hotcakes. A World War II veteran living in California,

he had purchased a shop that sold a wide variety of products including bicycles. He got tired of selling model airplanes and other

nickel and dime items. He decided to spruce up the shop and sell only Schwinn bicycles.

The change worked and Schwinn bicycles began to fly out the door. The visiting Schwinn

marketing team liked what they saw and took the idea of dedicated Schwinn

dealers back to Chicago to sell to the boss.

The marketing team also did their research to back up their impressions. After painstakingly going through sales records, they found that 27 percent of Schwinn retailers accounted for 94 percent of sales (Crown and Coleman, 1996). To make matters worse, Schwinn marketing materials such as the catalogs at the end of this article were sent to small shops that sold less than one Schwinn per year.

Freezing out other retailers was not an easy decision. They represented

a significant share of Schwinn’s sales. For instance, B. F. Goodrich sold many

different products including Schwinn bicycles. In one notable conversation with

his marketing team, Frank W. Schwinn said, “I guess you’re going to lose me

that (B. F. Goodrich) account.” At the time B. F. Goodrich had 1700 different locations selling Schwinn bicycles. He also was friends with Alfred Sloan of

General Motors who had developed a single-brand dealership model for selling

cars. He accepted the advice of his younger

managers and the “Authorized Schwinn Dealer” was born.

Schwinn also was not idle in developing new bicycle models.

They launched the extremely popular Black Phantom in 1949. This was not much different

than the earlier autocycle, but they added some fancy styling features that made

it popular among consumers. The Black Phantom was advertised as having all the

popular options, such as a spring fork, chrome fenders, horn button on tank,

built-in fender light, and white wall tires. The model became quite popular

during the 1950s and today they are a collector’s item.

|

| The Black Phantom Was Introduced in 1949 and Was Instantly Popular (Image: Schwinn Catalog, 1952) |

Schwinn was facing increasing competition from Europe starting in the 1950s. The European bikes were lighter and featured 3-speed internal gears. True or not, they also were perceived as being somewhat fragile.

To meet this European competition, Schwinn developed a line

of middleweight bicycles. The top of the

line middleweight was the Corvette, a name mimicking the popular sports car. The lightweight bicycles were still not selling

very well and in 1954 middleweight bikes like the Corvette, Jaguar and Panther

filled the void for older children and young adults.

|

| 1955 Schwinn Corvette and Middleweight Bicycles Introduction (Image: 1955 Schwinn Catalog Front Cover) |

These middleweight bikes became an immediate hit and led sales barely one year after their introduction. They were marketed as being just as nimble as their European counterparts but more reliable. Because of their popularity, Schwinn had created a whole line of bikes for those that were not enamored with the stylish, yet heavy, balloon tire bikes.

Schwinn had hit on a winning strategy. To meet the increased

market demand of the 1950s, Schwinn increased and more finely tuned its advertising

and marketing reach, expanded the availability of a wide range of high-quality

bicycle models, and concentrated sales to clean, modern stores. Competition

would soon come, but in the 1950s Schwinn became the bicycle of choice for many

Americans. The popularity of Schwinn would make it a national icon and carry it

through the next several decades.

Good Times Roll in the 1960s

Schwinn was poised on the runway and ready for takeoff. After

years in the making, in the early 1960s the three legs of a strategy to improve

sales were finally in place. These included investments in innovative marketing

techniques, strengthened manufacturing capacity, and improved efficiency of the

company’s dealer network. Frank W. Schwinn had begun implementing all these

changes ever since the 1930s. In the 1960s, they had come to fruition and Schwinn

was ready to “Let the good times roll” (Crown and Coleman 1996).

Schwinn increased sales by about 15% per year during the

1960s. Schwinn started the decade

selling 500 thousand bicycles in 1960 and reached close to 900 thousand by 1970

(Petty 2007). The company also was not resting on its laurels because it was busy

introducing popular new models. There

were some clouds on the horizon, but they would not materialize until much

later.

Amid the good times, Schwinn hit a bump in the road in 1963.

After contracting cancer, the company’s long-time owner and president Frank W.

Schwinn passed away at the age of 69. In the short term, this wouldn’t have any

impact on the success of the company. He had put in place a competent team of

managers that—at least for the time being—could carry on without him.

Frank W. Schwinn had built the company into a bicycle

powerhouse in over 30 years. He introduced a glitzy line of children’s bicycles

that sold very well from the early 1930s through the 1960s. In the late 1930s,

he produced world-class lightweight bicycles—including the Schwinn Paramount—that

were ahead of their times. In the 1940s

he recruited Hollywood and television stars to promote Schwinn as the best

bicycles in the world.

Frank W. Schwinn also was constantly innovating on the

factory floor by investing in new manufacturing techniques. He also turned

Schwinn from a private label maker of bicycles sold in retail stores to an

iconic national brand backed by an exclusive dealer network. His contributions

were not only beneficial for Schwinn but also for the entire bicycle industry.

|

| Schwinn 1960s Dealership and Sign (Image: 1966 Schwinn Catalog) |

Frank V. Schwinn took over the role of his father. He was a hands-off manager and let others manage their divisions. He began emphasizing marketing and financing at the expense of modernizing the factory. He felt most comfortable in finance and sales but now had to run the whole company. This approach had some success in the beginning but over time it began to take its toll on Schwinn.

Schwinn still was a company that could spot trends and

quickly produced new bicycle models. In 1962 an executive at Schwinn named Al

Fritz noticed a trend in California of boys riding funny-looking bicycles. They had small wheels, long seats, small

frames, and riser handlebars that looked like Texas longhorn steers. With this

unusual configuration, he was surprised to see kids doing instant wheelies and

riding on the rear wheel for blocks.

With thoughts on a new model, Al Fritz brought the California

components back to Chicago to develop a prototype. Everyone at Schwinn who rode

the prototype was amazed that such an awkward-looking bicycle could handle so

well. The factory quickly cranked out a new line of bikes to satisfy what they

rightly anticipated would be a new bicycle craze. Al Fritz came up with the

name Sting Ray. The Sting Ray was an instant hit 42 thousand were sold by 1964.

|

| New Schwinn Sting-Ray Craze in 1965 (Image: 1965 Schwinn Catalog) |

By the end of the 1960s, the beginnings of an adult bicycle boom had begun. With the 1950s kids now entering early adulthood and the environmental movement in full swing, road bikes were starting to become very popular. Schwinn had been making lightweight bicycles for decades without much sales success. Given this experience, they should have been well positioned to develop new lightweight models for adults. They had a middleweight line that was aimed primarily at teens. New models for adults called the Varsity and Continental had been developed in the early 1960s but with their dropped bars were not very popular.

These Varsities and the Continentals were road bicycles made

from the traditional heavy steels, the same material used in producing the kids'

bicycles. They relied on existing factory technology to weld the frame for the

Varsity and Continental. The frames were built with innovative electro-forged

welding techniques which gave the bicycle frame very strong with a smooth look

at the joints. The problem was that this technique could not be used with the

newer, lighter chrome molly tubing.

The Varsities and Continentals did prove to be popular among

teenagers who were fairly rough on their bicycles. These models were a good fit because they had

very strong, almost indestructible frames. Unfortunately, the bicycles were

heavy compared to European imports because they could not be used with modern

alloys such as chrome-moly. As a result,

the Varsities and Continentals made few inroads into the adult market. Only 1

in 20 Schwinn bicycles were purchased for use by adults.

With favorable exchange rates,

European and a trickling of Japanese manufactures began to sell large numbers

of bikes in the USA. By 1970, European imports reached about 2 million bicycle

sales compared to close to 1 million by Schwinn. Despite the popular models bought mostly for

children and teenagers, the market share of Schwinn bicycles sold in the USA

continued to shrink from an all-time high of 25 percent in 1950 to 12% by the

end of the 1960s (Petty 2007).

After the death of Frank W.

Schwinn, the three legs of the stool that had built Schwinn bicycles began to wobble.

With catalogs featuring places like Disneyland and 20th Century Fox,

marketing continued to be a Schwinn strong point. However, management had begun

to ignore the need to retool its factory. Manufacturing techniques were

beginning to become outdated. Sales were still at all-time highs, but with the

market share declining, Swhinn’s dominance in the bicycle industry was on the

wane.

|

| Schwinn 1966 Catalog Features Disneyland (Image: 1966 Schwinn Catalog) |

Due to the inability to handle the new lightweight steels, Schwinn began to look for alternative ways to sell lighter bicycles. Instead of modernizing to make the new bicycle lines in-house, in the early 1970s, the decision was made to import lugged lightweight bicycles from Japan. Schwinn was not alone in this practice. To take advantage of lower wages and favorable exchange rates, many US companies were beginning to manufacture products in Asia. As an example, Radio Corporation of America changes its name to RCA Corporation to recognize its manufacturing of a large range of products and expansion into other countries.

The seeds of an end to the Schwinn family dynasty as a bicycle manufacturer had been sowed after Frank W. Schwinn’s death in the early 1960s. The company's struggle to maintain pace with the rest of the bicycle industry would turn into reality in the 1970s. Many were quick to blame the generation of family managers after Frank W. Schwinn but the rise of low-cost manufacturing in Asia was challenging for all American companies. “Made in America” was giving way to made in Japan, Taiwan, and eventually China. Schwinn was still a force in the early 1970s, but the bloom was coming off the rose of an iconic American company.

Slow Response to New Trends in the 1970s

Schwinn was riding high. The bicycle sales boom in the early

1970s meant that they could do no wrong. Bicycle sales for children continued

to be strong. Schwinn had a slow start in producing the new popular 10-speeds

but picked up steam by successfully selling the new Varsity line of bicycles to

young adults. In 1971 Schwinn hit a new high in bicycle sales of 1.2 million bicycles

and this included 326 thousand 10-speed bicycles (Pridmore, 2001). This

amounted to a whopping 25% market share in 1970.

|

| Schwinn Varsity Sport, 1974 (Image: 1974 Schwinn Catalog) |

|

| Schwinn and Raleigh Compete for Adult Bicyclists in the 1970s (Image: Doug Barnes of 1971 Raleigh and 1983 Schwinn Badges) |

Frank V. Schwinn had a more relaxed management style and relied heavily on seasoned managers such as Al Fritz and Ray Burch. Frank V. Schwinn reasoned that the existing crop of managers had met decades of earlier challenges and there was no reason that this trend could not continue. Thus, during the rest of the 1970s, the company was in the hands of Frank W. Schwinn, a non-confrontational manager that tried hard to accommodate opinionated managers and shifting family alliances.

Unfortunately, Frank V. Schwinn had a heart attack in 1974

not long after being appointed as head of the company. He would be in charge of

the company until 1979 but psychologically never would get over his brush with death.

Schwinn needed a more decisive manager to deal with the

company problems faced during the mid-1970s. The company was in the middle of

dealing with growing imports. Frank V. Schwinn had to decide whether his

company should continue a “Made in America” tradition that had served it well for

several decades. He also had to deal with an aging and antiquated Chicago

factory. Despite all of these problems, Schwinn

was still a major force in the bicycle industry in the USA throughout the

decade.

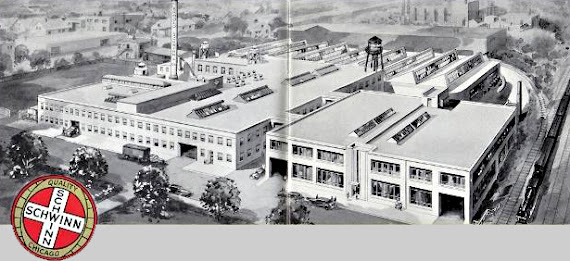

|

| Schwinn's State of the Art Factory, Circa 1940s (Image: Made in Chicago Museum Website, Access 2021) |

During the mid-1970s, the American bicycle industry was

evolving from a business of supplying bicycles only to kids to also providing

them for adults. Schwinn should have been ready for this trend because Frank W.

Schwinn had tried to steer his company towards adult bicycles as early as 1939. He had introduced the Schwinn Paramount with

expectations of a boom in sales that never materialized.

In a twist of fate, just as adult bicycle sales were exploding,

Schwinn did not have the desired lightweight models available in high volumes

for its customer. The factory had invested heavily in electro-forged welding machines

that were not suitable for modern types of steel. Breaking with their “Made in America”

tradition, Schwinn temporarily solved this problem by importing bicycles from

Japan and Taiwan. Schwinn was not alone as

many other US manufacturers were beginning to outsource manufacturing to East

Asia.

Schwinn imported its first Japanese-made bicycle model as

early as 1972. Al Fritz had traveled to

Japan to dictate the specifications for the new Japanese-made Schwinns. What

emerged were two well-made bicycles worthy of the Schwinn name. One used the historic

World label, a moniker first used by Schwinn in the 1890s. The second model was

named the Schwinn Le Tour, a road bike destined to become a classic.

|

| First Advertisement of Schwinn "Approved" Le Tour (Image: 1974 Schwinn Catalog) |

Schwinn also was slow to embrace this new type of bicycle

emerging from a trend in California. In California, teenagers and pre-teens

were fitting new seats and handlebars on their Stingrays to use them for both

tricks and racing. The trend caught on and they were called BMX bicycles.

Schwinn was aware of the trend but saw it as a flash in the

pan. Frank Schwinn was hesitant to enter the BMX market due to safety concerns.

Schwinn also worried that they could not put a lifetime guarantee on bicycles ridden

to their limit on BMX courses. Crashes and mangled bicycles were part of the

rough and tumble world of BMX races.

Skip Hess, the founder of Mongoose, was quoted as saying

“The (Schwinn) people in Chicago only heard the echo” of this new Trend (Crown

and Coleman p. 109, slightly reworded). He

established a new company named Motomag that first sold stronger wheels to modify

existing Stingray-style bicycles. He even sold some as accessories through

Schwinn bicycle shops. In 1976, he established a new company called Mongoose to

offer a complete line of BMX bicycles. This was a very good move because sales

of BMX bicycles in the US surged from 140 thousand in 1974 to 1.75 million by

1977 (Crown and Coleman 1996).

The 1982 film ET (ExtraTerrestrial) illustrates the intensity

of the BMX craze. A gaggle of boys riding BMX bicycles returning ET to his

spaceship for his flight home evaded police by racing down streets, over curbs,

and down hillsides. They eventually came to a police roadblock and magically

rose in the air avoiding ETs capture. An iconic Hollywood image emerged as they

sailed through the air with their bikes silhouetted against a setting sun. In

earlier years, Schwinn would have been all over this new craze.

|

| Highlighting BMX Craze, Bicycles Carry ET to his Rocketship Ride Home, 1982 (Image: 1982 Film ET) |

|

| Schwinn's First BMX Style Bicycle is the Scrambler, 1975 (Image: 1975 Schwinn Catalog) |

In 1980, this was followed by a higher quality BMX bicycle

called the Sting. Schwinn was able to squeak out a 7 to 8 percent market share

of BMX bicycles by 1980 but this was too little and too late. By then, other

upstart manufactures of BMX bikes had captured the market and established their

names. Schwinn’s BMX bicycles were left in the dust.

Another change in the bicycle industry confronting Schwinn

was a mountain bike craze emerging in Marin County, California. In a second

ironic twist, the creators of the mountain bike in trend-setting California

were modifying old 1930s Schwinns because of their durability and coaster

brakes. Races down a rugged fire lane

were taking place on a course they called Repack. They rode the old Schwinns

hard and fast. What emerged from these races was a new style of bike that we

know today as the mountain bike.

Schwinn was not convinced that the mountain bike craze would

turn into sales opportunities. They couldn’t have been more wrong. This meant

that the California entrepreneurs had an opening to develop bikes with

suspension for riding on mountain trails.

Joe Breeze, Charlie Kelly, Gary Fisher, and Tom Ritchey were avid Repack

riders and realized that the old Schwinns being raced on the mountainside course

had their limitations.

|

| Joe Breeze on Repack and a 1949 Schwinn Autocycle with Drum Front Brake (Image: Charlie Kelly's Website, Accessed 2021) |

As if this wasn’t enough, Schwinn would be challenged in

nearby Wisconsin by a new company called Trek. Sounding more like a hiking

company, the company decided to build “Made in America” lightweight bikes to

satisfy the growing demand for bicycle touring. They featured lightweight steel

and brazed lugged frame construction.

In the late 1970s, Trek with its narrow range of specialized

bicycles was no threat to mammoth Schwinn. Trek kept waiting for Schwinn to put

the hammer down on them by building a line of competitive lightweight bicycles,

but it never happened (Crown and Coleman 1996). This gave Trek some breathing room

to diversify from its original touring bicycles to other models that would be

in direct competition with Schwinn.

Trek at one point even made an overture to buy Schwinn in

the early 1980s that was summarily rejected.

The creativeness of the new company would continue during the ensuing

decade when Schwinn was dealing with internal organization problems.

In 1979, Frank V. Schwinn relinquished his authority to

manage the company to Ed Scwhinn, Jr, a 30-year-old great-grandson of founder Ignaz

Schwinn. After just less than a decade running the company, Frank V. Schwinn

had enough and wanted to retire. He would retain the title of chairman and

chief executive until he died in 1988 but Ed Schwinn, Jr. would take over day-to-day

management of the company.

A young Ed Schwinn, Jr. as the heir to the Schwinn family

business would have to be very quick on his feet to meet all the challenges confronting

the company. Schwinn had a bicycle line that was identified as a children’s

product. The Japanese were increasingly making

inroads into the American market. Upstart

niche bicycle manufacturers abounded. The Chicago factory was aging and in need

of being upgraded or replaced. On top of

all this, the Schwinn family wanted to retain full control of the company and

therefore did not want to bring in private investors to pay for needed

manufacturing upgrades.

|

| A Young Edward Schwinn, Jr. Takes Over in 1979 (1983 Schwinn Lightweight Bicycles Catalog) |

Ed Schwinn, Jr. quickly ordered a management shakeup, The new

chief executive surrounded himself with financial specialists. According to old-timers, “Regression analysis

clashed with the glad-handing old boy school culture. (Crown and Coleman 1996, p142)

“ Ed Schwinn,

Jr. broke with long-time managers

including the well respected Ray Burch and Al Fritz. The likes of a 25-year-old

brother-in-law was hired to take their place along with a host of financial

analysts and marketing specialists.

Schwinn had been managed by one person for over 40 years. Now

Schwinn had to deal with the turnover of two chief executives in the space of 8

years. Ready or not, a youth movement was underway at Schwinn. The new team running

Schwinn was young and brash. The

question would be whether the new management team assembled by a young Ed

Schwinn, Jr. could prepare the company for the coming decade.

Sales had decreased to 900 thousand bicycles by 1980. The new managers would have to deal with increasing competition, an aging factory, and whether to rely on imports as the mainstay of new bicycle production. The 1980s would prove to be a critical test for the Schwinn family business.

The Tumultuous 1980s

Edward Schwinn, Jr. has been roundly criticized for the

demise of Schwinn Bicycles as a family company. Although not all of his

decisions were stellar, the blame was somewhat unfair.

Family businesses rarely last longer than the three

generations, so the surprise is that the Schwinn family-owned bicycle company

lasted so long. Jonathan Ward (1987) in

his work on family business succession indicated that 30 percent of businesses

last through the second generation. This figure is reduced to 13 percent by the

third generation. Only 3 percent of family businesses are still alive and

kicking by the fourth generation (Zellweger, Nason, and Nordvist 2012). Edward

Schwinn, Jr. was a fourth-generation president of a family business.

Although these figures are a bit dated, the odds of family business survival are generally accepted to be low for several reasons. The charisma of the early founder fades and business conditions change. The next generations often have other interests. Successors may not be qualified for the job. Finally, nepotism and family feuds are inevitable.

Schwinn was not the exception to this rule. The Schwinn family bicycle company was very strong for two generations. The third generation Schwinn manager Frank W. Schwinn did not have the drive of his father.

|

| Second and Third Schwinn Generations: Father Frank W. Schwinn (Center) with Sons Frank V. (Right) Edward, Sr. (Left), Late 1940s (Image: Made in Chicago Museum ND) |

The fourth-generation manager Ed Schwinn, Jr. placed too much emphasis

on financial models and was not interested enough in modernizing the family

factory. He also had to deal with a bicycle

industry in the throes of manufacturing globalization. These conditions would challenge

even the most nimble companies.

Eward Schwinn Jr. wanted to carry on the Schwinn family

business tradition but he also was handicapped by the Schwinn family trust. Not

uncommon in an era of paternalism, in the 1920s the founder Ignaz Schwinn had

set up a family trust for the company that contained both shares and of the

company and its name. The stock shares of Schwinn were then passed down to the oldest

son of each generation. The consequence was that by the 1980s, the stock of the

company family trust was divided up among 16 family members.

|

| Schwinn Catalog Cover, 1980 (Image: Schwinn Catalog, 1980) |

Edward Schwinn, Jr. only owned about 3.4 percent of the

company himself and family members held the rest. Even though he made all the major

business decisions for Schwinn, he also had to deal with family politics.

The sometimes unhappy family shareholders felt entitled even

though they were not contributing anything to the company. Although they did

not take large amounts of cash flow from the company, a big problem was that the

family wanted to keep Schwinn entirely under private control. The Schwinn

family did not want to dilute their shares by offering stock to the public or

other major investors. Appointing an outsider as a chief operating officer or

offering stock to gain much-needed capital for modernization was out of the

question.

The first trouble for Schwinn came in the early 1980s with a

factory strike in Chicago. The “Made in Chicago” badge on Schwinn bicycles was always

a matter of pride for the company. In its heyday, the factory produced almost

everything in a Schwinn Bicycle but the steel tubing. Up through the 1950s,

continual investments were made to upgrade the capability of Schwinn to build

bicycles entirely from scratch in Chicago.

The factory floor in Chicago was an amicable place to work

in the 1940s and 1950s. Frank W. Schwinn made it a point to know the factory

workers by name. Workers trusted Schwinn and did not require a detailed written

contract. An element of paternalism was evident between Schwinn and its employees

but it was always correctly assumed that Schwinn would take care of its

workers. This tradition was eroded in the 1960s and 1970s with the rise in the

volume of Schwinn sales.

|

| Schwinn Bicycle Assembly in Chicago Factory, 1945 (Image: Made in Chicago Museum, ND) |

The new Schwinn workers rightly worried about their job security.

In this environment, outreach by unions to organize the factory was met with a

positive response by the workers. After the death of Frank W. Schwinn, the

communication gap between the factory and Schwinn management widened. This

culminated in a 1980 vote by workers to unionize the Schwinn factory.

Both Edward Jr. and Frank V. Schwinn felt betrayed by the

workers. When approached to negotiate a contract with the new union, Schwinn

management stonewalled. The strike was settled in 1981 and the union made modest

gains in salaries and benefits. The dye had been cast in the minds of the

Schwinn managers. The vote to unionize had reinforced Schwinn’s desire to close

the Chicago factory. The factory was closed in 1983 but it would be a pyrrhic

victory for Schwinn (Crown and Coleman 1996).

With the winding down of the Chicago factory, in the early

1980s Schwinn increasingly looked to overseas manufacturers for bicycles. During the factory strike, Schwinn turned to

a small bicycle manufacturer in Taiwan called Giant. Anything but a Giant, the

company desperately wanted to produce bicycles for the dominant company of the

era. Once Giant got its toe in the door, Schwinn was quickly won over. Schwinn

managers realized that low-cost, high-quality manufacturing in Asia rather than

in the USA was a real possibility.

Giant further endeared itself to Schwinn during the strike

by delivering on a promise to pick up the slack in manufacturing capacity.

Giant agreed to provide Schwinn with an additional 80 thousand bicycles. By

1984, Giant ratcheted up production to 500 thousand bicycles for Schwinn which

accounted for about two-thirds of Schwinn sales (Crown and Coleman 1996). To a financially-oriented manager like Edward

Schwinn, Jr., once the quality of the Gaint-produced bicycles was confirmed,

reducing costs while at the same time eliminating the headaches caused by the

Chicago factory seemed like a no-brainer.

Schwinn was hooked.

Despite the successful imports, Schwinn was not ready to

give up its “Made in America” branding. While winding down the antiquated

Chicago factory, in 1981 the company opened a new bicycle production facility in

Greenville, Mississippi. The company had high hopes for the new factory. The

region was anti-union so they imagined that their labor problems would be solved.

Thoughts of putting an expanding new company called Trek out of business with

high-quality “Made in America” bicycles swirled in their heads.

Debates raged inside Schwinn about whether to abandon its

“Made in America” identity. Low-Cost Mississippi seemed like the solution. Schwinn

eventually decided to produce its high-quality bicycles in the Greenville factory

and low-quality bikes in Asia. This was a reasonable strategy and similar to

one being followed Trek.

|

| 1983 Schwinn Le Tour Made in Greenville, MS Factory but with Chicago Badge (Image: Doug Barnes) |

Schwinn made a last gasp effort to correct the problems with

the Greenville plant. Edward Schwinn, Jr.’s brother Richard Schwinn volunteered

to move to Mississippi to oversee the factory. He made significant progress in

improving the quality of bicycles coming from the plant but it was too little

and too late. The new factory in Greenville Mississippi never generated a

positive cash flow and also was destined to be closed. Trek and Specialized

were snapping at Schwinn’s heels. In retrospect, the failure to upgrade the

Chicago factory to make high-end bicycles was a profound mistake.

Schwinn was not idle in developing new bicycle models. After

being late to the party, Schwinn finally developed a mountain bicycle that

could live up to its reputation. They first rolled out a mountain-style bicycle

in 1982 called the Sidewinder. Sidewinders were nothing more than modified

Schwinn Varsities or Continentals with large tires and regular handlebars.

|

| Schwinn Sidewinder, 1983 (Image: Schwinn Catalog, 1983) |

|

| Schwinn Sierra and High Sierra, 1984 (Images: Schwinn Lightweight Bicycle Catalog, 1984) |

In 1983 Schwinn also produced its first catalog dedicated

exclusively to BMX bicycling. They introduced the Predator series the same

year. All predators had chrome-moly

tubing. This finally established Schwinn as a maker of high-quality BMX but it

was too little and too late. Mongoose

and Diamondback had become established competitors in the BMX market.

|

| First Schwinn BMX Catalog Cover, 1983 (Image: Schwinn BMX Bicycle Catalog, 1983 |

The Air-Dyne was an innovative machine relying on specially

designed fan blades instead of a traditional wheel to provide resistance to

pedaling. At the same time, it created a

gentle breeze for the rider. Schwinn sold a high of 67,000 Air-Dynes in 1986

with a high price tag of $595. The profits

from the Air-Dynes helped keep Schwinn afloat during a time of declining bicycle

sales.

|

| Schwinn Air Dyne, 1985 Schwinn Lightweight Bicycles Catalog, 1985 |

The factory in Hungary was partially successful in producing

the Schwinn Woodlands, but many of the imported bikes had to be warehoused due

to quality issues. For a company

struggling with cash flow and being supervised closely by its banks, this was

not the time for Schwinn to gamble on becoming a global player. Schwinn pulled

the plug on the unsuccessful venture in 1991 just one year before bankruptcy.

Schwinn saw its relationship with its Taiwanese manufacturer

Giant turn from a partner to a competitor. Giant helped save Schwinn during the 1981

strike at the same time that it was launching its new bicycle brand label. By

the late 1980s, Giant started to aggressively market its own bicycle brand in

the USA and increasingly became a competitor to Schwinn.

Schwinn saw the writing on the wall with Giant. The company began

to diversify its Asian manufacturing. To accomplish this, in the mid-1980s Schwinn

purchased a one-third share of a China Bicycles factory in Hong Kong (Crown and

Coleman 1996). The goal was to reduce its reliance on it main Asian

manufacturer Giant. With the Hungary and Hong Kong ventures and with the

Greenville plant, Schwinn planned to be secure a bicycle supply base that was

not overly dependent on one manufacturer.

Schwinn’s “Made in America” reputation undermined its

ability to pivot its entire production offshore. The “Schwinn Approved” label did

not fool any customers. They understood that Schwinn bikes made in Asia were just

like all the other imports. The “Made in America” quality branding no longer

distinguished Schwinn from its competitors. In retrospect, the move to

manufacture bicycles in Asia was a necessity given the growing globalization of

manufacturing but it didn’t fit in well with Schwinn’s branding. Schwinn had started

the decade as an entirely “Made in America” company and ended it with 80% of its

bikes imported from Asia under the “Schwinn Approved” label.

|

| "Schwinn Approved" Imported from Asia Voyageur, 1980 (Image: Schwinn Catalog, 1980) |

Looking back, Schwinn had suffered from a thousand cuts during

the 1980s. Schwinn was juggling a lot of balls to keep the company afloat. This

included the closing of a longtime factory in Chicago, starting a new factory

in Greenville, Mississippi, buying a 40 percent share of a plant in Hungary,

and purchasing a one-third interest in a factory in Hong Kong. Spurred by the

era of globalization, by the end of the decade Schwinn outsourced most of its manufacturing

to Asia.

Schwinn also was being challenged by new competitors in niche

markets such as mountain, BMX, and high-end road bicycles. Japan and Europe

also were competing with Schwinn in the US market. This was made worse by Schwinn

abandoning its wholesalers who then were freed up to market these other bicycles

brands.

Schwinn also didn’t want to part with all of its tried and

true children’s market and this meant that bicycle shop inventories

proliferated out of control with too many bicycle models. Selling children and

adult bicycles was an awkward mix for Schwinn dealers. During the late 1980s,

all of these companies were competing for a shrinking piece of the bicycle pie.

Bicycles sales declined by 20 percent from about 12.6 million in 1987 to 10.7

million bicycles in 1989 (National Bicycle Dealers Association, 2021).

In the face of all these challenges, Schwinn would have been

required to get many things right to stay as a family business. A young Edward

Schwinn, Jr. had created a youth movement among Schwinn management bringing in financial

specialists that had sometimes limited experience in manufacturing. The new

team was not up to the job.

At the end of the 1980s, bikes coming in from overseas piled up in Schwinn’s warehouses. Eventually, Schwinn was not able to pay the Asian manufacturers for these unsold bicycles. The bankers perceived the trouble at the Greenville factory and the misadventure in Hungary as a hit to their confidence that Schwinn could manage its financial woes. This combined with lower Schwinn bike sales set in motion a series of actions that put the company under financial stress starting in the 1990s.

Family Business Bankruptcy in the 1990s

The Schwinn brand finally found a good home. In 2001, Schwinn was purchased out of bankruptcy by a more bicycle-savvy company called Pacific Cycles. Pacific Cycle was purchased and became a part of Dorel Industries in 2004. Dorel focused on reviving the Schwinn name in 2010. Under Durel Sports, the iconic Schwinn brand was transformed into a bicycle company that sells low-cost models in big-box stores such as Walmart, Target, and Kohl's. This strategy was quite successful despite Schwinn's history of antipathy towards such large retailers. Besides Schwinn, Dorel marketed many familiar brands of bicycles including Cannondale, GT, and Mongoose.

Schwinn has been No. 1 in all the brand surveys I’ve seen going back 40 years. While their bikes are lower in quality and price than when they were selling through bike shops [in their heyday], Schwinn’s mass-retail models have slowly gotten better over the years. So if consumers want bikes for under $300 or so, the demand is there.

In 2021, a new chapter begins with the sale of the Schwinn brand to Pon Holdings, a manufacturer of high-quality bicycles. Pon Holdings emphasize that one major reason for its purchase of Dorel Sports was that Schwinn is one of the major known brands of bicycles in the USA. The fate of the Schwinn brand is still unknown, but being part of a larger company with deep pockets may lead to innovation and perhaps even to upgrading their offered bicycles.

The Netherlands is one of the leading bicycling countries in the world. The Schwinn name may have found a good home in the Netherlands. Only time will tell whether or not the iconic Swhinn brand is now in good hands. The fate of Schwinn is now entrusted to a Dutch company.

References

Andrews Fred. 1996. “It’s a Schwinn” New York Times. New York.

Ward, Jonathan. 1987. Keeping the Family Business Health.

New York: Palgrave MacMillan

Thanks for posting this. Very impressive history. Just back from visits to Bicycle Heaven and the Bicycle Museum of America.

ReplyDeleteI visited Bicycle Heaven about 5 years ago. it was my second visit and I enjoyed it thoroughly. I have a new update on the bankruptcy of the Schwinn family business in 1993 as a separate blog item on the site. Pretty interesting story.

DeleteAre you aware that the Bicycle Museum has all of the Schwinn Co. financial records, board minutes, etc.? I own a Schwinn Homegrown MTB (c. 1999) and a 1966 Raleigh Carlton. Both i purchased new. Neither gets ridden much now, but can't part with them yet.

ReplyDeleteHere is a comment that I received via email. I thought it was interesting so I am posting it here with the author's permission.

ReplyDeleteBegin Comment

I just discovered your stories about Schwinn. They are great! My father was a Schwinn dealer in Sedalia, MO for years. I think he was the longest running original owner Schwinn dealership in the country until he closed. You have some great information about Schwinn and its struggles with unions and supply. I remember reading a Schwinn Reporter and it included an article about Schwinn buying land in Oklahoma because it was a right to work state. Schwinn never built anything there and moved on to other projects.

I understand Schwinn’s feelings about having a union but wonder why management didn’t investigate what other companies were doing related to union relationships etc. I think the Schwinn union was UAW. I remember visiting the plant on North Kostner for bicycle school in 1974. I was 19 and had never been on a tour of a manufacturing plant in my life. While touring the plant it seemed a bit inefficient in the way things were done. The big thing that was touted was the new frame plant – it was located a few miles away. Folks boasted how the frames were assembled and primed and loaded on a truck that had a scissor mechanism – like a food service truck at airports loading planes – that would enable the frames to be unloaded on the second floor of the plant and then begin the process of becoming a bicycle then boxed and ready to ship. I worked in economic development for the city of Sedalia, MO in the late 1970’s. Fruehauf located its subsidiary wheel plant Kelsye-Hayes in Sedalia as a nonunion facility. There was a labor force that could do the work plus a community college that was actively working with new companies to teach skills needed by companies. It is still going today but not part of Fruehauf or any affiliated companies. I guess Schwinn tried this but made bad choices on locations.

I sure enjoy your stories. Thank you for writing them.

End Comment